A really interesting session today with lots to think about! Lottie started out by highlighting that we have created an ableist norm and ‘pop in’ elements of disability and that furthermore, we tend to limit inclusion of disability to ‘inspiration porn’ – terms which Lottie went on to define later in the session.

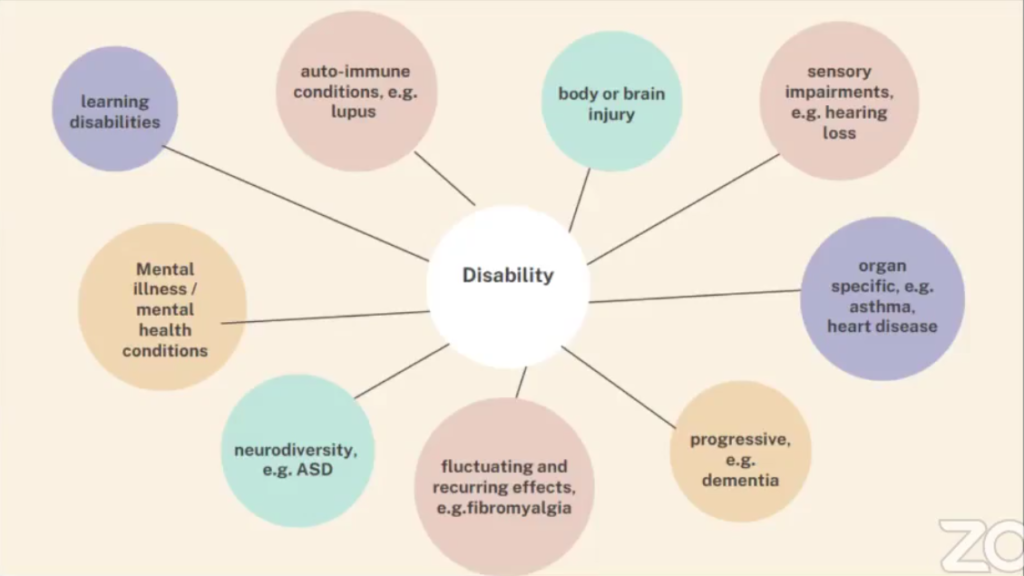

Lottie identified some key concepts in the area of disability and two wich are key in terms of how they’re represented in materials: the medical model of disability looks at what is ‘wrong’ with the problem; the social model of disability says people aren’t disabled by their difference, but by societal factors which may be physical, attitudinal or institutional. A final concept she mentioned is ableism: the unfair treatment of disabled people.

She then talked about what can come under the umbrella of disability, as can be seen in the image to the right. There are diverse conditions and within each impairment, they may be differeing views about how people would like to identify themselves.

Why is it important to represent disabled people in educational materials?

Probably a lot of our students are affected by disability, either personally or within their family. Hugh commented that people need to see themselves, the challenges others face and how they deal with them. Lottie added that textbooks establish a kind of ‘normal’ and are often seen as an authority, having been created by established institutions or government agencies.

If students can’t see themselves in the materials, they’re less likely to engage with the topic and perhaps even with the learning process. However, it also helps everyone become global citizens and learn aout lived experience.It’s also important that people aren’t being represented as ‘lesser than’ through the materials. UN research suggests that around 15% of the world’s population live with disabilities.

What examples of disability have you seen in ELT materials?

I’ve certainly noticed students in wheelchairs in some YL materials recently but there weren’t many comments in the chat for that question, which perhaps suggests that people haven’t seen much representation!

We tend to have limited representation of disability, most of which are visible disabilities like being in a wheelchair. We also tend to limit disability to particular topics, such as Paralympic athletes. Furthermore, the focus is often on the person’s disability or follow particular themes such as people requiring help or people who are inspiring and succeed ‘in spite of’ their disability.

Lottie recommends watching Stella Young’s TEDtalk, “I’m not your inspiration, thank you very much”. She added that one of the big tropes that we rely on in materials is including disabled people who inspire non-disabled people.

How can we represent disability better?

Lottie highlighted six things we can do:

- Avoid the non-disabled norm, stereotypes and ableist tropes

- Represent throughout the book or your materials and avoid tokenism

- Show a range of visible and invisible impairments and different types of people

- Take a person-first approach and focus on the person, not the impairment

- Show disabled people as active, independent people

- Show disabled people authentically, naturally, living everyday lives

Representing disability: artwork

We looked at some examples of artwork which is quite overt in its representation of disability, but which could work without drawing attention to the disability. We can also use images which show disability in a more subtle way. For example, the image which Lottie chose for the webinar ad from Disabled and Here. She also suggests that representationsof disability could be included in the background of images or considering whether images show accessible environments. Some photobanks are getting better at inclusive images, but Lottie also shared a number of more independent photobanks such as pixabay, Unsplash, Pexels and Disability: In.

Representing disability: texts and audio

When we create texts, we can consider how inclusive and representative the materials are. For example, focussing on the person’s achievements first or telling the story from the person’s perspective and showing them as a whole person. Lottie also talked about the need to talk to people whose disability you’re including to ensure that you get their lived experience right.

If we just stick disability in particular topics, it can either problematise it or make it very tokenistic. Lottie argues that you can include disability in any topic. For example, on the topic of technology, you could produce a text on writing good alt text for images online or on the topic of films and TV, you could feature films about or by disabled people – but avoid the trope of a non-disabled person reviewing the film or series and being inspired by the character.

She also suggested how we can show that disability is a part of a person’s life. For example, in a dialogue between two people who are about to leave the house, one of the characters says they need to grab their inhaler. This could then be highlighted through the teachers’ notes to raise awareness. We chatted a little then about whether we need to point out disability when it is implicitly included and Lottie said that it could be left up to the teacher if the option is there through the notes.

We also considered some cultural restrictions: in some countries and cultures, disability is still very stigmatised and materials need to be adapted for particular contexts. There was also a question from Dan regarding the grading of language – for example, inhaler. Lottie says ideally we would decategorise this language to enable it to be included at any level. As she says, the CEFR is based on frequency…but frequency for whom?