Another popular choice in the poll, with a select group there on the day to share their ideas.

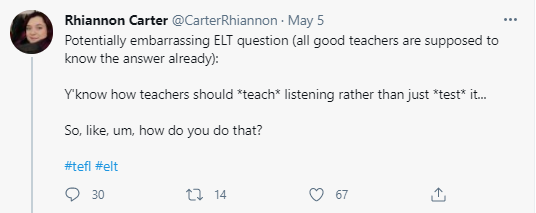

Part of the inspiration for this topic came from a recent Twitter post from Rhiannon Carter, which I think has unfortunately since disappeared. As you can see, there were lots of responses to it.

During the chat, we talked about how our learners feel about listening and the fact that many feel demotivated in different ways:

- I have a good C1 level but I really struggle when I watch Netflix.

- If I see the tapescript, I know all the words…so why can’t I understand when I listen?

- I speak the language well, but if someone asks me something on the street I have no idea what they said.

“We don’t realise we aren’t teaching.”

There was a definite feeling as we chatted that it was a few years into teaching before we realised that we weren’t really supporting our learners that well in the classroom with listening. Perhaps this is due to the fact that on pre-service qualifications, we often focus more on the staging of a listening lesson than on skills development?

The idea of lowering the affective filter and learners not needing to understand everything was mentioned and it’s worth reading Scott Thornbury’s Zero Uncertainty post on the topic. We also identified that there’s a need for more bottom-up processing but that it’s important not to get too stuck looking at the basics – BALANCE is the key.

Bottom-up processing

We talked about how encouraging learners to notice discourse features makes speech much more accessible. Filler words (such as like, kind of*, anyway) and features of connected speech are often the most frequent things we look at.

*Interestingly, one teacher mentioned when doing this bottom-up work in class, their student was able to notice that this kind of was different to another kind of…great to see learners engaging with language in this way.

Thinking about filler words, it’s interesting to bring it back to the learners’ L1 and ask what type of fillers they use when speaking. Noticing how certain words or phrases are just there as a feature of speech might make it easier to ‘ignore’ them and focus on the important content.

Sandy Millin has a great activity in ELT Playbook for dealing with listening difficulties and extends the areas which learners might have problems in when working with authentic texts: grammar, vocabulary, cultural knowledge, connected speech, intonation, accent, dialect or variety of English, and background noise.

On the topic of background noise, we talked about how learners sometimes complain during a speaking activity in the classroom as they struggle to concentrate when there are six other pairs also having conversations around them. The fact is, this is a very natural situation for us to find ourselves in and probably some of us struggle to focus on what the person we’re talking to is saying when we can hear other people chatting around us (and not because their conversations are necessarily more interesting! #FOMO).

We also said that another feature of real natural speech is for one person to give feedback as the other is speaking, i.e. the listener interjects (right, ah-ha, yeah) over the other person. Though coursebooks are introducing more of these natural interjections in recorded material, they still tend to not be simultaneous. In films and TV shows as well the dialogue tends to involve much more turn-taking than happens naturally.

We can do a lot to pre-empt problems our learners might have but one thing to add here is that while we might think we know what difficulties learners are going to have, it’s always worth reflecting post-listening as well to see if our predictions were correct – otherwise we might spend time focussing on the wrong aspects of the listening.

And on the subject of predictions, we questioned the value of pre-listening prediction activities if students’ predictions are incorrect and not identified as such by the teacher. If we predict something is going to be said, we will probably try to listen for that. And it seems that lower-level learners stick more closely to their initial hypotheses whereas stronger learners might be more able to identify if their prediction was correct.

Although even pre-pandemic many teachers encouraged learners to listen to the audio on their own devices rather than playing it to the class, the pandemic and online teaching has made many of us much more willing to incorporate tech into the classroom. A benefit of having learners listening on their own devices is that they can identify the exact point when there’s something which they don’t understand (although this can obviously also be done in a while class situation with learners putting their hand up, though they might feel more reluctant to do so). Having learners note the exact second when they have difficulty makes it much easier for us to go to that point in the audio and work on it with them. (A guilty confession of mine is getting to the end of the listening and asking, ‘Was there anything you didn’t understand?’)

One teacher mentioned making use of voice messages with her learners between classes and taking time at the beginning of the lesson to check if there was anything they hadn’t quite got.

Approaches to deal with the issues above

1) I’m sure we’ve all been guilty of suggesting our students ‘just watch TV in original version’ in order to improve their listening skills at some point! Streaming services are a great resource as it makes it much easier to pause and rewind or add subtitles than in the past. One thing we did suggest in the chat is choosing one minute of the programme to really focus in on and do that bottom-up work, and sitting back and enjoying the rest of the show in a more relaxed way. There are more ideas in this post from Joy of Languages and there was also a post from Cambridge University Press which we shared in the Hub a while back.

Chiara Bruzzano has done lots of work on listening and in this open-access post from ET Professional, she talks about the benefits of watching TV with subtitles.

We spoke a little about listening being receptive pronunciation work and also reminding learners that how they hear something in one context is just one way it might sound. Using sites like Youglish and Playphrase.me (which might now be a subscription site) we can expose learners to the same phrase said in different accents or different contexts.

You should also check out TubeQuizard which has clips specifically focussing on pronunciation for listeners.

2) We discussed the benefits of working with the tapescript before listening every once in a while. A suggestion for using the tapescript was for them to mouth along as they’re listening to help them notice chunks of language and pauses, sounds which are ‘lost’.

Another suggestion for making use of the transcript was for learners to listen to a chunk and try to identify how many words they hear, then compare that to the tapescript. Again, this encourages them to notice chunks. This can also be done by blanking out the chunk which you want learners to focus on if they’re working with the transcript whilst listening.

3) Interestingly, we wondered whether this was more of an issue for learners in an ESL context, rather than people not living in an English-speaking country. However, we said that as immigrant teachers, it’s probably something we have experienced ourselves and so can use that as a way of bringing the topic into the classroom.

We talked a little about context and how it’s very rare in day-to-day life that you are involved in listening when you don’t know the context: conversations with friends, listening to a podcast or the radio – these are examples of communication where there is rarely a sudden tangent. In fact, the time when you probably don’t have any context is the typical ‘You overhear two people talking on the train’ J Similarly, when we do listening comprehension activities in class, aside from the wonderful lead-ins we do, the comprehension questions themselves will add context to the task and give the learners clues about the content.

Another aspect which we talked about was giving learners more effective ways of interrupting or asking for clarification in conversation. ‘Excuse me, could you possibly repeat that?’ is not the quickest way of getting someone’s attention, nor the most natural.

Thinking about interrupting, we also noted that some cultural awareness is important here – depending on the learners’ context, they may not feel comfortable interrupting a conversation.