This week we were joined by Mark Carver, a lecturer at the University of St. Andrews. He lectures on the MSc TESOL and runs the DProf TESOL – a PhD level programme for teachers looking to carry out practice-focused research.

There’s a lot of academic research about what counts as quality education in teaching, but less so specifically related to ELT. Mark sarted off the session by asking why it was important to theorise quality, highlighting that on many initial teacher training courses there tends to be a distinction between learning teaching and learning to teach. Learning to teach is seen as more of a craft, rooted in practice; learning teaching is a long-term development path which enables you to progress in your own way as a teacher.

There is obviously quite a difference in the types of programmes for becoming a teacher in different countries, but globally the CELTA and CertTESOL, which are relatively short courses, would perhaps be seem more at the learning to teach end of the scale.

Whilst these initial training programmes are fairly closely monitored, generally speaking it can be difficult to identify why we think a programme is high-quality. Furthermore, Mark highlighted that dominance in a market may be perceived as a mark of quality – but in imitating these courses you may be institutionalising biases or prejudices within them.

Mark went on to talk about some of the governing bodies in ELT, who came together to discuss quality education. He noted that it is often easier to identify what makes a bad course, and offered a serious of questions which potential trainee teachers might ask when choosing which course to follow:

- Who provides it?

- Is it accredited? (And by whom? Is there an ongoing inspection process?)

- Is is on a qualification framework?

- Does the awarding body have clearly defined procedures for monitoring the course against rigorous criteria?

- Are the admissions criteria and application procedures for the course clear and easy to understand? Is it possible to fail and do they only accept participants with a reasonable chance of success?

- Is it equivalent to 100+ hours contact?

- Does the course provide opportunities for observation and for supervised and assessed teaching practice?

- Does the awarding body manage a clearly defined appeals and complaints procedure for course participants?

As we’ll see later though, Mark suggests that these are factors which should already be a given on a good course and identifies further areas to look at in order to find a high-quality course.

There are also questions around the type of assessment which takes place on the course: some may be a practicum-based course with supervised teaching practice in which you are expected to meet certain requirements; you may be expected to create a portfolio of your lessons and the theory behind the choices you make in your planning and delivery; it could be a more theory-based course with assignments and less emphasis on practice.

Adams and McLennan talked about teacher development as identifying, doing and knowing teaching. At the initial level, you ‘pass’ as a teacher: you can act the part and follow routines and procedures. The next step is learning the pedagogy specific to your subject or age range, which also involves learning what’s not done within your specific group. Moving up, we learn to look at the ways things work in the local environment but link that to the wider context, becoming a much more reflective practicioner.

Another way which quality is sometimes measured in teacher education is double inference: student results are analysed and a correlation between high grades and quality teacher development is identified. However, there are other factors to consider, such as teacher retention and health, student satisfaction and graduate employment.

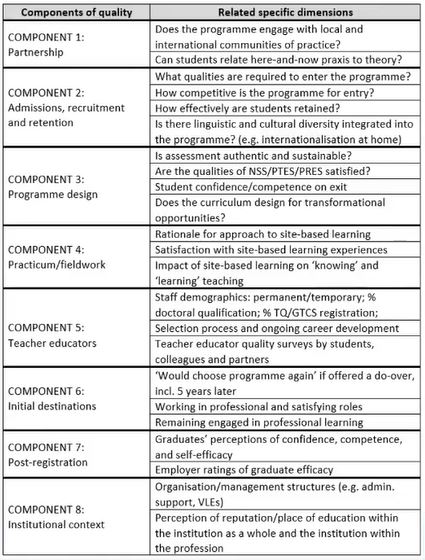

Mark went on to talk about a project that he has been involved in to look at eight components which a teacher development programme can demonstrate high quality in, such as the professionalism of the educating team; admissions, recruitment and retention; and the programme design. On the right are these components adapted specifically to ELT.

He also talked about ELT professional development in Scotland, where he’s based, and some of the challenges of teacher development programmes – such as the fact that ELT is only recognised as a secondary subject.

To round up, Mark looked at the type of things potential trainees should look for in a high-quality teacher development programme – assuming those earlier questions have all been answered positively. This includes whether they are likely to have a ‘smoothly-run’ experience, taking into account the timeliness of responses to emails or a general feel for the place if they are able to visit the site beforehand. Other factors are transparency from the course provider in terms of who will be tutoring on the course and their credentials, as well as whether they are engaged with the profession and on their own developmental path; and the opportunity to get feedback on how the course may benefit them as a professional, such as the career pathways of other graduates.

Mark’s work is ongoing and he’s interested in further developing the framework to other levels and looking at how different courses can be integrated into the framework. The DProf TESOL which he’s been developing is designed with this framework in mind. Mark is also involved in a couple of upcoming events which you might be interested in: for anyone who is carrying out research, he’s hosting a webinar open to all in November on carrying out interviews and focus groups. And in March next year, he’ll be taking part in BAAL’s panel event, Navigating the academic job market.

1 thought on ““I know it when I see it” – what counts as high-quality teacher development in ELT?”